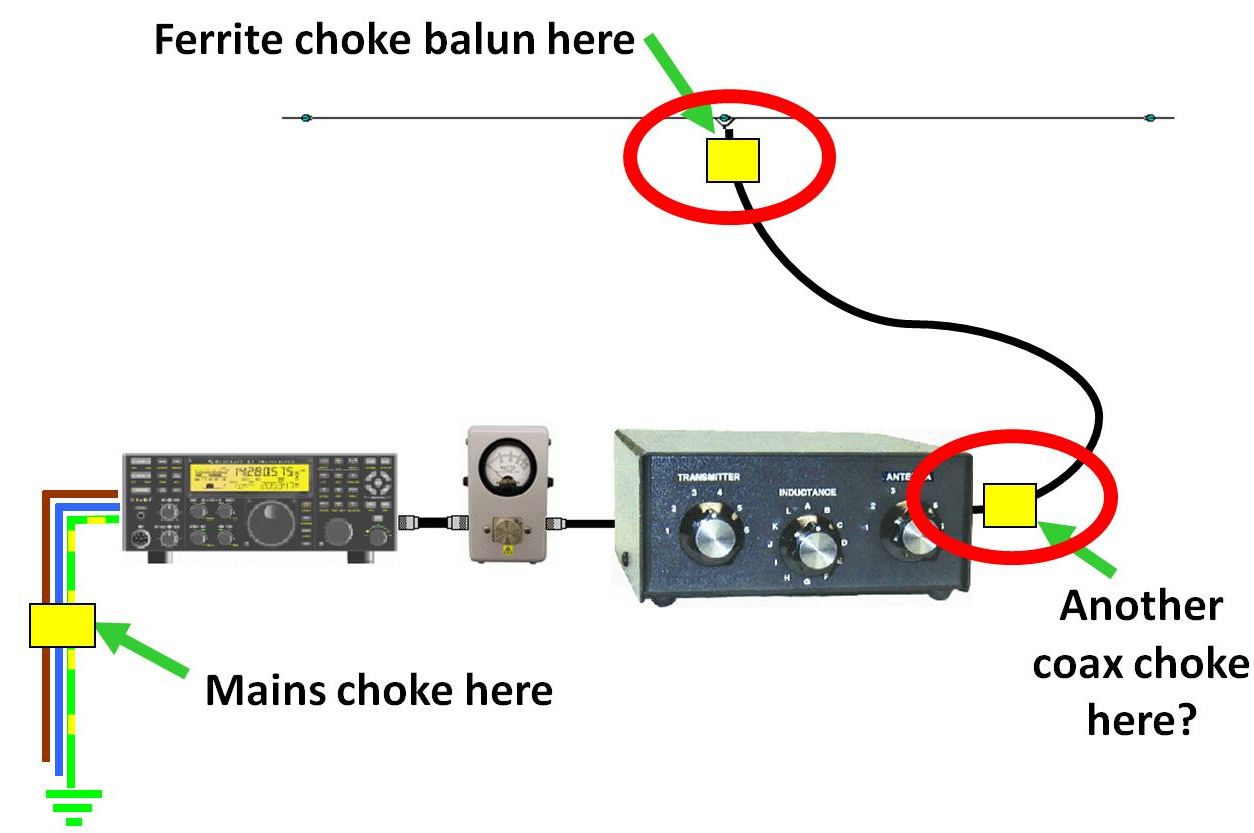

This is a common theme from several of my talks over the years about Ferrite Chokes and Baluns. By expanding the topic into a blog format, I hope to be able to explain it in more detail, and add some FAQs as time goes on.

This well-known image originated with Walt Maxwell W2DU, the author of many articles about transmission lines. It brings out several important points.

- The inside of a coaxial cable truly is “private” – completely screened from the outside world. This is one of the rare statements that can be handed to absolute beginners as a simple fact, and still remains valid all the way through to graduate-level EM physics.

- The private interior of coax is due to the skin effect which means that, at RF, current flows only on the surfaces of conductors.

There are many confusing illustrations in textbooks that make some people imagine the skin effect only applies to electrical conductors of some particular shape and size, or in some particular type of circuit. That isn’t true! The best and most generalized derivation of the skin effect I have been able to find is reproduced here. All the high-level EM physics and maths leads to a simple and very powerful conclusion:

Whenever and wherever an RF current is flowing (regardless of the circuit configuration, regardless of the reason) the skin effect will always be present.

RF current will always be forced to flow very close to the outer surface of the conductor. There is no net current flow into or through the thickness of the material.

- Because we know the skin effect will always be present, we can use that as a starting point when tracing RF current pathways on complex shapes such as coaxial cables and shielded loops. Suddenly, the whole topic of shielding (and what you need to do to make it work correctly) will begin to make sense!

There is one condition, though: you have to hold onto that idea consistently. Many of the myths in RF engineering arise because people aren’t being logically consistent. They imagine they can switch these basic ideas on-and-off to suit their own preconceived notions… and physics just ain’t like that.

- In coaxial cables, the skin effect in coaxial cables means that the outside surface of the shield is a completely separate conductor from the inside surface.

- The outside surface of the shield is part of the outside world. This is where the so-called “common-mode” currents flow.

Keeping Count of Currents

(This section contains detail to prove the overall conclusions. If you’re reading this for the first time, skip down to the Summary below. Then come back when you’re ready.)

There are five different current labels in the diagram above, so let’s simplify this:

- On the antenna, I4 and I5 are the currents at the two terminals of the feedpoint. Textbooks often show these as equal – but when we connect a feedline, I4 and I5 may not be equal any more.

- Inside the coax, I1 is the current flowing on the surface of the centre conductor. I2 is the current flowing on the inside surface of the coax shield. The centre conductor is entirely surrounded by the shield, leading to very strong electromagnetic coupling between these two conductors. The consequence is that I1 and I2 are exactly equal and opposite. (Strictly speaking this is an approximation, as distinct from a true ‘law of physics’, but in real-life coax I1 and I2 will be equal within a small fraction of a percent.) This means we can write: I2 = I1 (no minus sign because the arrows point in pposite directions).

- The junction point X is where the inside and outside surfaces of the shield meet together. Kirchhoff’s Current Law says that all current arriving at and departing from this point must sum to zero. Noting the directions of the arrows for I2, I3 and I5, this means that: I2 (arriving) = I3 + I5 (both departing).

We can rearrange this equation to say: I3 = I2 – I5. - Because we already know that I2 = I1, and I4 = I1, it follows that: I3 = I4 – I5.

- So, any difference between the two currents I4 and I5 at the antenna feedpoint will be routed onto the outside surface of the coax shield to become the common-mode current I3.

- Those are a lot of observations to keep in mind, but they all lead to one simple conclusion.

Summary

- Because the currents I4 and I5 in the antenna are never quite equal, they can be mathematically resolved into a differential-mode component and a separate common-mode component.

- However, a coaxial feedline will physically do the same thing! At RF, where the skin effect creates a third conductor on the outside of the shield, the pure differential-mode component of the incoming two-wire connection will automatically be routed into the private, shielded interior of the coax to become I1 and I2. Meanwhile the common-mode component is routed separately onto the third conductor, the outside of the shield, to become I3.

- If you can block the common-mode current I3 by using a common-mode choke, you will force the antenna feedpoint currents to become much more equally balanced.

And that’s the private life of coax.